Want Light Rail? Think MDRS.

Light rail has the chance to be a defining feature that will shape our city. However, at a cost of $3-4 billion, obtaining funding will be tough — regardless of the flavour of government. NZTA’s expenditure intentions are set to progressively move further and further away from current Crown funding and NZTA revenue, with a $6 billion deficit by 2030. At the same time, we have a background of potential local government rates caps, a government unconcerned with public transport and the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission recommending a greater focus on transport maintenance and renewals, and a smaller role of brand new infrastructure as a proportion of GDP in the future. This places light rail in a precarious position where transport funding for new infrastructure is tough to obtain, except for those with exceptionally strong strategic alignment and business cases. However, the recently released National Infrastructure Plan provided some hope.

The National Infrastructure Plan

Last month, the Infrastructure Commission released the Draft National Infrastructure Plan which laid out a framework and strategy for infrastructure into the future. To it, Minister Chris Bishop said:

“Improving the way we plan, fund, maintain and build our infrastructure is critical to boosting economic growth and increasing productivity and living standards, and so the Government welcomes today’s draft report by the independent Infrastructure Commission.

The Government is determined to improve New Zealand’s infrastructure system and to work alongside the industry and other political parties to establish a broad consensus about what needs to change. I’ve encouraged the Commission to brief all political parties as they develop the draft plan.”

This means that there will be greater scrutiny to projects, but also greater certainty that broader transport priorities wouldn’t just chop and change depending on whatever government is in power. Chris Bishop seems determined to ensure that this plan works and is followed through, which is why it was so encouraging to see that of the first round of projects, Christchurch’s Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Plan, was one of only four transport projects endorsed by the Commission at stage one, where there is strategic alignment and it clearly solves an existing issue. This means that in the face of greater scrutiny, MRT has passed the first hurdle in achieving funding — its single best chance for ever being completed. However, more projects will be submitted to the Commission — which will essentially compete with MRT — and as it goes to stage two, it will face its greatest challenge: proving value for money.

Mass Rapid Transit’s 2023 Indicative Business Case

Indicative business cases provide a high-level overview of options, deliverability, potential costs and benefits. MRT’s Indicative Business Case sets out an excellent vision, though the benefits and patronage projections are, to be quite frank, underwhelming.

The Bus Rapid Transit Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) is between 1 to 2.8, and the Light Rail option is between 0.8 to 2.3 when factoring in wider economic benefits. However, it is worth noting that light rail can generally expect greater land value uplift and around 25% higher patronage than bus rapid transit options. These BCR’s are rather uninspiring — cromulent, but uninspiring. Projects with similar price tags but worse BCR’s have been funded, however with greater scrutiny and cost pressures, we cannot expect that to be the case with MRT.

One of the largest shortfalls is the patronage projection. This shows that at 2051 passenger projections at the AM peak, double decker bus buses at 5-min headways would be more than enough, only excluding between Papanui and the Bus Interchange, coming from the northern end (heading from Dickeys Road to City to Hornby) — these projections are fairly encouraging, though they could still be better.

However, coming from Hornby to the City to Dickeys Road is disappointing and paints MRT as nearly unnecessary. From this direction, double decker buses are good enough nearby all the way, except between only Riccarton and Hagley Park in the most optimistic scenario. This does not build a good case for MRT. The patronage suggests that MRT may only be required between Papanui and Westfield and does not build a shining endorsement of building MRT from Hornby to Belfast.

What this means for MRT in the Infrastructure Priorities Programme Stage 2

As the draft National Infrastructure Plan endorsed MRT at Stage 1, it is likely that business cases will continue to be funded. To this, there are uncertain aspects that will be critical to MRT being recommended in Stage 2, and ultimately, if MRT is funded at all.

First, is the unavoidable impact of the inflation in construction costs that have occurred since 2023, which is invariably higher than CPI inflation and potentially higher than the assumptions baked into the BCR. This makes it all-the-more critical that, second, patronage projections improve significantly for the next business case. It cannot be stressed enough how critical this business case is for MRT as planned ever being built, and improving patronage projections is our main lever at play to enable this.

A Poor Alignment with Land Use

Population density surrounding the stops, connecting public transport routes and cycleways are key factors in how many people will actually use the route (i.e. patronage). From looking at the map below, it’s no secret that the alignment with land use and MRT at the point of this business case was very unambitious, especially west from Westfield Mall. This is worsened by Councillors voting down mixed-use and medium density zoning (MDZ) in Sydenham, Carlton Mill, St. Albans and Edgeware in the first portion of PC14 — all accessible to the MRT route. However, the Christchurch City Council currently has a decision to make for the final portion of PC14, which is the best chance we have to get MRT to Stage 2: Medium Density.

Housing Minister Chris Bishop instructed the CCC to make a decision on Medium Density Residential Standard (MDRS) by 12 December, either to adopt the standards across the whole city (as was previously instructed), or opt-out — with a catch. Bishop and MHUD required any Councils that opt out to zone for 30-years of feasible housing capacity under a high population growth scenario, plus a 20% contingency. Significantly, not long before this requirement, StatsNZ reviewed their population growth targets (which the government is statutorily required to plan for) to model that population growth will be substantially higher than previously thought. Therefore, the target that the Council will need to reach is high, and with significant time constraints. If they don’t decide by December 12, the ball is in Bishop’s court to zone the entire city to MDZ. To be clear, this would have been a good move — however, the quota is a much better scenario than opting out altogether.

Over the coming months — possibly even just weeks — Councillors will decide where to fill the feasible housing capacity target. Initially, Council staff provided four potential scenarios they may want to choose: one, along public transport corridors; two, surrounding existing high density zones; three, aligning with the Greater Christchurch Spatial Plan; and four, a scenario that goes slightly beyond the Greater Christchurch Spatial Plan which adds some MDZ near high frequency bus routes to essentially ‘fill-in’ the Orbiter bus route.

Option one was seen as too ambitious; no-go. Option two was a no frills option that hit the quota, made sense and not much more. Option three had the most interest and was where the room was leaning to. Option four was also a bit too ambitious. While a decision hasn’t been made, it will be soon. Councillors have the ability to go with a completely different option, or a variation; building consensus either in public, or private.

MRT’s Red Herring: Route Designation

In a recent workshop, Councillor Andrei Moore brought up zoning alongside the MRT corridor. The answer, however, brought us back to a Qualifying Matter (zone exemption/variation) that failed to be approved by Bishop following the first PC14 decision — MRT route designation which requires new buildings on the corridor to be set-back from the street. Staff explained that from their perspective that: one, medium density is not the ideal residential typology along MRT, 6+ storeys would be; two, it is best to not zone for MDZ near the MRT corridor until they have the route designation to reduce the need to purchase land to widen the corridor; and three, by the time they do protect the corridor, they will likely be required to upzone along public transport routes as part of Bishop’s Going for Housing Growth policy package anyway. While at first glace, this approach makes sense, it is problematic and potentially detrimental for MRT going ahead.

Firstly, it can take 5–10 years before developments start to take full advantage of new plan change rules. A couple of years of MDZ before introducing more permissive zoning is unlikely to result in much loss of potential 6+ storey buildings by the time MRT is built. Even so, the idea of avoiding 3-storey zoning because you want 6+ storeys — when the more permissive and higher demand Central City is not seeing many 6+ storey developments — is hard to justify. In all likelihood, even if we enabled 6+ storeys near MRT, the vast majority of new buildings would still be around 3 storeys.

Another key factor is the timing of the MRT business case. Zoning certainty — and, by extension, population growth certainty — is needed to make informed patronage projections. By the time Going for Housing Growth policies are implemented (which, if they follow the timeline of PC14, may take years), the business case will likely already be complete, resulting in less-than-ideal patronage projections.

Finally, as will be detailed, the premise that route designation is required at all seems questionable and poorly justified:

In a report by MHUD that outlined the evidence behind the decisions Bishop made to approve, or disapprove of the Council’s PC14 decisions, it recommended to not approve route designation as part of PC14. During the hearings for PC14, MHUD, NZTA, Ōtautahi Community Housing Trust all opposed it.

NZTA ‘questioned whether this is the most appropriate method for achieving integration of land use and transport planning’ and that it ‘reduces the potential for development capacity along the [MRT corridor]’.

Kāinga Ora criticised the framing of the corridor protection as means to make MRT easier to implement, rather, it is for amenity outcomes. Furthermore, a Council planner stated that the route designation is, ‘aimed to ensure adequate space for tree planting along the road frontage (even though tree planting was not mandatory) and to prevent permanent structures hindering future transport improvements. The [designation] was intended to enhance amenity and ensure new builds did not compromise future transport options. It imposed more stringent setbacks than the MDRS’. The Council evidence to implement the designation was subsequently described as ‘unpersuasive’ by the Independent Hearings Panel because the Council ‘failed to demonstrate that trees or landscaping could not be accommodated within the existing road reserve’. ‘The proposed 4 metre setback for tree planting was seen as inconsistent and not compelling. The IHP also found that the Council’s analysis understated the costs and overstated the benefits.’ ‘The Council’s approach was criticised for potentially leading to inconsistent landscaping and for not adequately evaluating alternatives’.

Finally, in a slam-dunk, the report said ‘While the Council sought an alternative recommendation to the [route designation] that restricts building within the road building setback along the proposed rapid transit route and considers the route is planned sufficiently to justify the QM, they did not propose to enable greater density and building heights of at least six storeys within the walkable catchment of these planned routes, as required by policy 3(c)(i) of the NPS-UD on the basis that the rapid transit stops on these routes are not sufficiently planned.’ In other words, MRT was paradoxically far enough along to restrict housing, but also not far enough along to enable the retail and housing that would complement and ensure the existence of light rail. You can’t have your cake and eat it too, or rather, you can’t have your cake at the same time as insisting that the cake isn’t ready to come out of the oven.

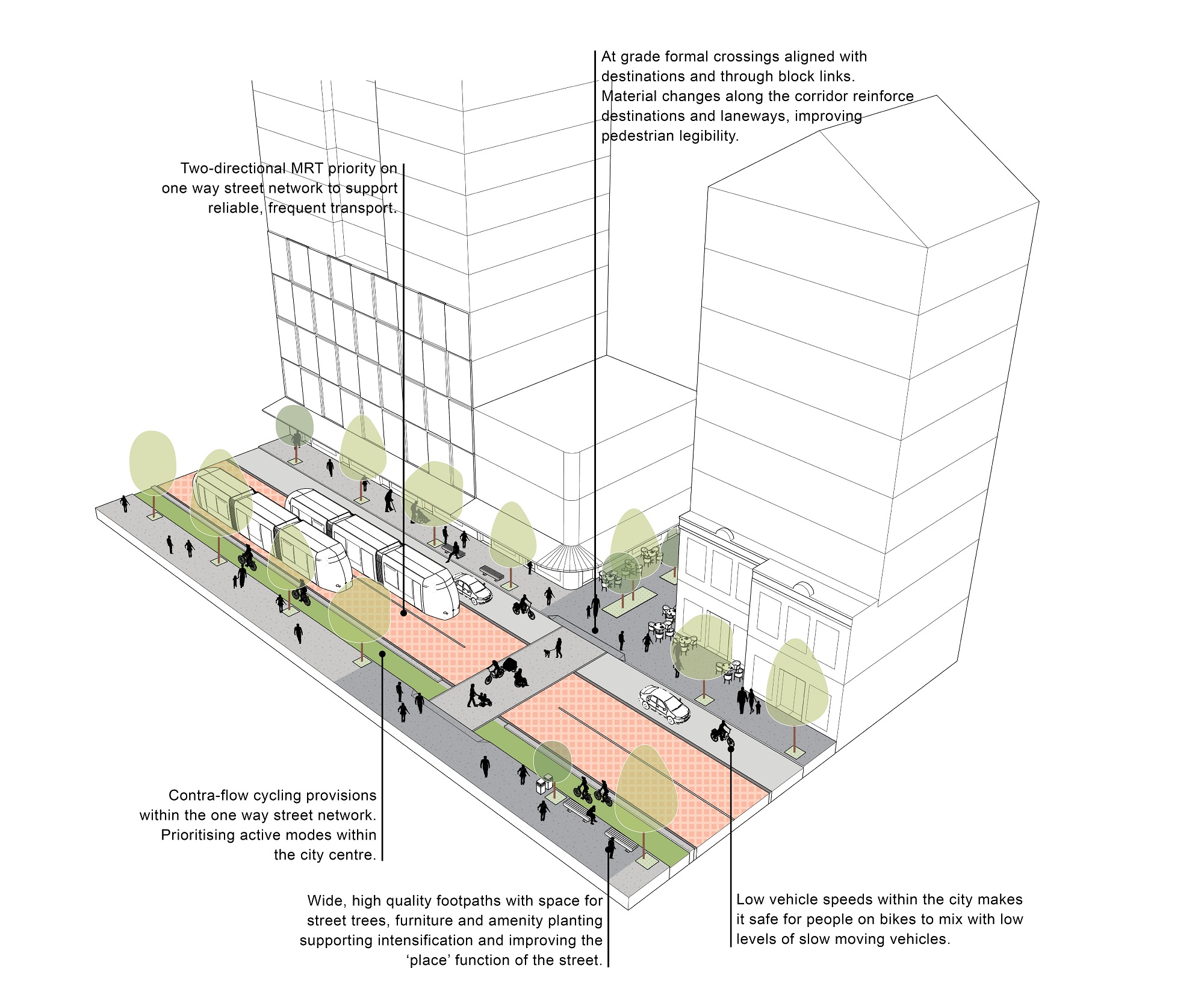

Even in the business case itself, all road layouts consider the existing road width, and there is no mention of setbacks being required along the corridor. It is a distraction to suggest that route designation is critical, when there is no compelling evidence presented to suggest that it is beneficial to the development of MRT and no compelling evidence presented to suggest that it is required to improve street amenity, nor a plan presented on how to do so. Rather, there is evidence to suggest that it actively harms MRT from achieving funding in the first place. It will actively harm the BCR, patronage projections and potential residential developments while presenting no clear benefit. Going for route protection over medium density zoning would truly be shooting ourselves in the foot.

The Way Forward

To put MRT on its best foot forward, to get a head start on vibrant, growing neighbourhoods, retail and job centres ready to embrace frequent and fast light rail, we must upzone as much as we can both along the MRT corridor, and near any connecting public transport and cycling routes. Building upon the plan Councillors and staff have made thus far, additions should be made at least between Church Corner and Hornby, Merivale and Papanui, Papanui and Belfast, and any other bus, or cycle route that will feasibly be used to connect to MRT. To be clear, we should absolutely improve street amenity too. A green, attractive corridor would complement light rail, attract people to it, and increase people's desire to live and be near it. Though going through the route designation path before upzoning may lead to MRT not being funded at all, with no guarantee of street amenity improvements, and worse urban design for the homes and retail along the corridor. If we want infrastructure that facilitates a growing, vibrant city, we must plan to allow us to become a growing, vibrant city in the first place.

Member discussion